Select any text and click on the icon to listen! ByGSpeech

ByGSpeech

ByGSpeech

ByGSpeech ByGSpeech

ByGSpeech

As of 2022, oil and gas contributed to nearly 45% of the energy supply in Africa, making them critical for energy security; coal, hydropower and biowaste are also vital energy sources. However, nearly 60% of African citizens lack access to energy, as power plants face mounting challenges and experience frequent power outages. This has prompted several governments, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Africa, and Nigeria, amongst many others, to prioritize addressing this challenge.

Recent instability in various pockets of the globe has caused commodity prices to soar, making oil and gas imports ever more expensive and leaving vulnerable populations disproportionately affected. Due to unreliable power from grids across Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a growing reliance on off-grid diesel generators as 17 countries, including Nigeria, Kenya, and Ghana, have more offgrid diesel generating capacity than grid capacity, with demand expected to grow annually by 5% until 2027.1 In West Africa alone, backup generators constitute 40 per cent of annual power consumption, according to the International Finance Corporation. This trend presents dire risks for African economies on several fronts as it increases carbon emissions and is expensive to maintain as inflation causes energy price surges. 2 These vulnerabilities and inordinate public debt further constrain African nations’ ambitions to develop their hydrocarbon potential, expand their energy independence, and create more revenue streams.

In this regard, member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council can aid the oil and gas sectors across African economies as Gulf states look to diversify their economies away from oil by investing in infrastructure, energy, agriculture, and mining in Africa. With wealth built from hydrocarbons, Gulf states can lend their expertise to African economies looking to make their sectors more efficient in Nigeria and Angola, for example. They can even lead exploration efforts in Senegal, Mozambique, and Uganda, amongst others who have made recent oil and gas discoveries.

Cooperation in Existing Markets

The oil wealth of countries like Angola, Nigeria, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea, where oil accounts for 40 to 60% of government revenue, draws parallels to Gulf economies, opening opportunities for collaboration. For instance, Nigeria, Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville, and Equatorial Guinea are members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), where Saudi Arabia and the UAE hold leading roles and can influence the hydrocarbon policies of some African economies.

The UAE contributed considerably to the oil and gas sector in existing African markets by developing port infrastructure through companies like DP World and AD Ports. In Angola, for instance, AD Ports signed agreements to modernize the port of Luanda in 2023 and is developing the Caio Deepwater Terminal at the Cabinda Port.3 Similarly, DP World, which operates 12 ports across the continent, signed a 20-year, $190 million concession to modernize and operate a multipurpose terminal at the Luanda Port. In 2024, DP World was awarded a contract to build a new 1.1 billion USD port at Ndayane, Senegal, encompassing a container terminal and dredging to increase the size of vessels it can accommodate.

Furthermore, the UAE has supported the oil and gas sector by transporting equipment across the continent. While ADNOC supplied supertankers to increase oil storage capacity for Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, P&O Logistics - a DP World subsidiary - has supplied hydrocarbon equipment to Nigeria, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea. Nigeria’s oil pipelines are inefficient and need urgent modernization to meet the industry's current needs. The UAE has shown interest in developing the supporting infrastructure when the UAE Ambassador to Nigeria, Salem Al Shamsi, led a delegation to invest in Nigeria’s oil exploration hosted by Petroleum Minister Heineken Lokpobiri. Nigerian President Tinubu and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman also signed investment agreements to revamp Nigeria’s oil refineries at the Saudi-Africa Summit in 2023 underlining that the Kingdom has also made considerable efforts in these areas.

New Oil and Gas Markets in Africa

Recently, African countries have made significant oil and gas discoveries that necessitate an influx of capital for exploration and supporting infrastructure. The World Bank estimates that 40 percent of global natural gas discoveries occurred in Africa between 2010 and 2020. Notably, Senegal discovered an estimated 15 trillion cubic meters of natural gas off its shore with Mauritania in 2015, which has the potential to address energy challenges, grow export revenues, and stimulate the economy through foreign direct investments. Senegal’s President Bassirou Faye is looking for partners who will invest in infrastructure to support the hydrocarbon industry for domestic energy and exports.

The GCC’s experience in existing markets demonstrates their ability and expertise to work across African hydrocarbon sectors and can inform their role in emerging oil and gas economies. For instance, the UAE’s long-standing engagement in Africa’s infrastructure prepares it to develop the new port in Senegal’s oil and gas hub at Ndayne, as the current inefficient port off the coast of Dakar dates back to 1862. This new port will support Senegal’s trade and demonstrates how GCC investments align with President Faye’s ambitions.

Uganda is adamant about becoming an oil-based economy after discovering six billion barrels worth of oil reserves in the Albertine Graben in 2006, with an estimated 19 billion USD extraction cost. Before it embarks on its extraction, Uganda needs infrastructure, including operation facilities, production wells, and refineries, which could exceed 15 billion USD, thereby challenging Uganda to finance these projects on its own.6 The UAE has already emerged as a vital infrastructure partner as Dubai-based Alpha MBM Investments is nearing an agreement to fund a 4 billion USD oil refinery in Hoima, which could process up to 60,000 barrels a day.

Qatar, as a global leader in the LNG field, actively explores offshore gas reserves across the continent, bolstering energy cooperation with Senegal, Mauritania, and Namibia. In 2024, Qatari Energy Minister H.E. Saad bin Sherida Al Kaabi hosted his Senegalese counterpart H.E. Birame Diop to discuss how Qatar can help develop LNG resources and energy infrastructure.8 In 2023, QatarEnergy acquired a 40% stake in Block C-10 offshore Mauritania, while Shell and the SMH hold 50% and 10%, respectively. The consortium is exploring oil at the Panna Cotta carbonate prospect by focusing on drilling to unlock Mauritania’s oil potential.

Following Namibia’s offshore oil and gas discovery in its Orange Basin in 2022, the nation grew closer ties to Qatar by signing an MOU in energy cooperation. Furthermore, QatarEnergy and Shell each hold a 45% stake in the PEL-39 Exploration license, while the National Petroleum Corporation of Namibia holds a 10% stake.10 Since then, Qatar has made three oil discoveries in the Orange Basin and continues its deep-water exploration, demonstrating its commitment to supporting this sector across African countries.

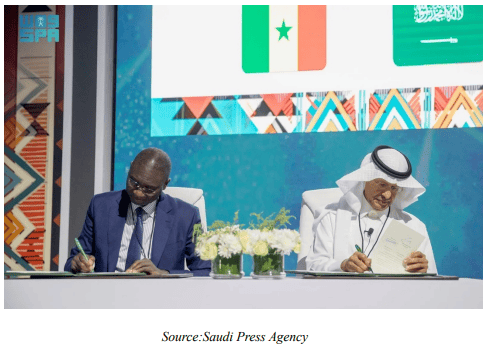

Saudi Arabia is bolstering its energy cooperation in Africa, especially with Senegal and Rwanda, which are revitalizing their hydrocarbon industry. Rwanda is determined to be an oil-producing country and has invited foreign oil and gas companies to lead exploration efforts in Lake Kivu, which borders Uganda’s Lake Albert.11 During the Saudi Africa Summit in 2023, Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz Bin Salman signed an MOU with Rwanda to support oil demand, increase efficiency in exploration, and enhance integration between petroleum industries.

In 2007, Ghana discovered its oil and gas potential and has relied on the Port of Takoradi for offshore exploration and production.13 The Saudi Development Fund has provided 12 million USD for its rehabilitation and expansion. According to Trading Economics, Ghana produces 200,000 barrels per day but aspires to increase its output exponentially. Red Sea Gateway Terminal (RSGT), a subsidiary of Saudi Arabian oil and gas company Xenel, was in advanced negotiations to develop a 120 million USD oil and gas service port in Takoradi. Through RSGT, the project’s infrastructure would have supported exploration, increased cargo handling capabilities, and furthered the GCC energy cooperation with Africa. However, in 2022, the Ghana Ports Harbour Authority awarded China Harbour Engineering Company the concession.

While the Gulf states have overlapping interests in contributing to oil and gas exploration in untapped African economies, the Takoradi Port in Ghana highlights the competition that Gulf states encounter from China, the largest bilateral creditor to Africa, which provides infrastructure, mining, and energy financing to various African nations.15 In another instance, Djibouti's government seized the Doraleh Port, operated by the UAE’s DP World, and handed it over to China Merchants Port Holdings in 2018, reiterating that China’s strong ties across the continent can undermine the GCC’s efforts to support hydrocarbons in Africa. The Gulf states face additional competition from Western institutions. For instance, the Grand Tortue, home to a significant offshore gas deposit between Senegal and Mauritania’s maritime borders, has drawn the interests of British-based BP, American-based Kosmos Energy, and Dutch-based Shell, which can constrict Qatar and Saudi Arabia’s interests in energy cooperation with Senegal.

The Case for the GCC

As the competition over African resources intensifies, the clearer case for the role of the GCC states needs to be made. The GCC-Africa relationship is mutually beneficial as Gulf investments align with their economic diversification plans while advancing African industrialization. African countries also require significant capital for their new industrial age, spurred by energy, mining, agriculture, and infrastructure. As Gulf states aspire to diversify their economies, these African sectors have become essential investment targets for the GCC. Gulf initiatives increase trade and value in the supply chain through oil refineries, trading port modernization, and airports, including the UAE’s Sharjah Chamber of Commerce and Industry which announced a new international airport near Uganda’s border with Kenya.

As discoveries in oil and gas can lead to the so-called Dutch Disease, whereby the rapid development of one economic sector leads to the decline of other sectors, the experience of GCC states in this regard could be beneficial. Senegal’s shift to oil and gas exploration for example, holds unforeseen impacts on the agrarian economy as FDI inflows will target hydrocarbons more than agriculture. To mitigate some of these risks, GCC members’ interest in agriculture, energy, and mining can certainly help. Saudi Arabia alone has consistently invested in Senegal’s agriculture sector with over 130 million USD of inflows.16 Senegal’s agrarian economy can further address the food security challenges faced by the GCC.

Gulf states offer a strategic advantage to African countries looking for financial relief. Western financial institutions, like the IMF, often impose conditions tied to governance and social reforms, while GCC countries present fewer financial barriers and faster access to capital. For instance, in 2024, the IMF delayed distributing a 600 million USD relief in Kenya after the court invalidated a Privatisation Act that would limit bailouts for struggling state-owned enterprises. Withholding these loans will raise Kenya’s credit risk and dilute investor confidence. In 2023, Ghana faced similar delays from IMF loans due to social reform issues; however, Gulf partners offer relief without stringent conditions as Saudi Arabian Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadan announced 530 million USD worth of financing for debt-distressed countries at the Saudi-Africa Summit.

As the Western powers adhere more to climate-conscious policies, there is a reduced appetite to invest in hydrocarbon exploration in Africa. Notably, the World Bank is hesitant to finance fossil fuel projects as it shifts to low-carbon investments.17 In 2023, President Akufo Addo decried the efforts taken to dissuade African countries--who account for less than 4% of carbon emissions-- from exploring their hydrocarbon potential by industrialized countries who account for over 70% of emissions, exposing an air of inequity amongst the two regions. Furthermore, President Faye is reluctant to allow foreign companies to extract natural resources and use them abroad when they are needed in the countries they come from. Given the Western reluctance to invest, tying investment with hurdles and specific terms and conditions, and an unfavourable history of resource exploitation, there is a strong case for Africa to turn instead toward the GCC as partners.Similar arguments can be put forward as far as China is concerned. Through Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, private and public sector entities have faced accusations of debt-trap diplomacy by granting large development loans to African economies, assuming they will not be able to repay. Once the country defaults on the debt, China gains leverage over strategic assets or economic discussions. Due to economic challenges, China—Africa’s largest bilateral creditor—has tempered its investments in Africa. In 2021, it announced a 40 billion USD commitment to Africa, which fell below the 60 billion USD pledged in 2018.

While China is reducing its investment across the continent, the GCC states are taking on a more active role. At the Saudi-Africa Summit in 2023, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman committed over 50 billion USD for investments, exports, and development projects in several countries. GCC-led investments exceed 100 billion USD and support human capital development, bolster multilateral trade, and increase output in underdeveloped sectors. As several leaders are looking for more equitable partnerships, there is ample opportunity for the Gulf states to increase their engagement in Africa.

Although a multi-lateral alliance between Chinese and Gulf governments could seem unlikely, collaboration is rife in the private sector. For instance, as South Africa battles a looming energy crisis, Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power is developing the Redstone power plant in South Africa; however, privately held SEPCO III China is handling the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC), demonstrating that it is possible to mitigate the competing interests for African economies.

In addition to developing the hydrocarbon sector, Gulf states have helped African economies embrace the global shift to clean energy. The GCC states’ expertise in this industry enables them to transfer more efficient technologies that are more climate-conscious. The UAE has championed renewable energy, for example at COP28 where it announced a 4.5 billion USD initiative to develop Africa’s green energy potential. Similarly, Saudi Arabia is promoting clean energy initiatives in Africa. Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salaman signed an MOU with Mauritania Energy Minister Nani Chrougha to enhance cleaner fossil fuel technologies like carbon storage and capture.19 The technology and knowledge exchange comes at an important time as Mauritania is developing its green hydrogen potential, demonstrating how Gulf states can help diversify Africa’s approach to the energy challenge.

Challenges Ahead

Africa’s political landscape remains dynamic, with 23 countries undergoing or preparing for elections in 2024. Political transitions pose risks to long-term projects, as seen in Senegal. In July 2024, President Faye annulled an $800 million water sanitation project led by Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power, citing high costs. Such examples highlight the precarious nature of executing longterm development projects in African markets.

Despite the strategic benefits that Gulf investments harbour for African economies, domestic sentiments must therefore be taken into consideration. As DP World neared signing a deal with Tanzania to upgrade the Dar es Salaam Port in 2023, civil society groups and political opposition parties grew apprehensive. Although Tanzania would retain 60% of the port’s earnings, dissenters argued that Emirati control of the port could threaten national sovereignty and undermine local management. Tanzania’s High Court dimmed the petition to challenge the port agreement; however, this case exemplifies the hurdles Gulf initiatives can encounter in African communities.

The global interest in developing resource-rich African economies has further placed African leaders in an optimal position as they have several foreign partners to choose from. As the Gulf states face increasing competition, they must nurture their ties to African countries to mitigate competing interests. The Gulf states’ multi-pronged approach seeking to support multiple economic drivers and usher Africa into a new age of industrialization is a good case as compared to countries like Russia or the United States that centralize their efforts in mineral extraction in the Lobito Corridor or Mali, for example.

The Gulf Cooperation Council has strategically positioned itself as a significant player in Africa’s oil and gas sector, leveraging its hydrocarbon expertise and financial capabilities to support African economies in developing their energy infrastructure. By investing in ports, pipelines, and exploration activities, Gulf states such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar are fostering longterm partnerships with African nations like Nigeria, Senegal, Uganda, and Ghana. These collaborations offer mutual benefits: Africa gains much-needed capital and expertise for its energy development, while the GCC furthers its economic diversification and geopolitical influence.

However, as competition intensifies from China and Western powers, GCC states must continue to present themselves as equitable partners, offering flexible financial support without stringent conditions. By prioritizing sustainable development, embracing clean energy initiatives, and addressing local socio-political concerns, the GCC can strengthen its position as a preferred partner in Africa’s industrialization efforts. Through its engagement, the GCC has the potential to become a cornerstone in Africa’s energy transformation, helping both regions navigate the challenges of a rapidly evolving global energy landscape.

Michael Wilson is a Researcher at the Gulf Research Center (GRC)